I had the extraordinary privilege to be graduated from the University of Nebraska College of Law on Saturday. I think this is the part where I'm supposed to sit back and reflect on this experience, but I haven't done any serious journal-blogging for quite awhile and don't really remember how to do it. Fortunately, I have a built-in template for this blog that should work swimmingly.

What?

Law degrees are as old as it gets in academia: the first vestiges of the juris doctorate were conferred by 11th-century glossators, schools of law that evolved into the medieval universities. *1 The latin literally means something closer to "teacher of laws," which actually tells you something about my current situation. I am a Doctor of Laws (and an Esquire), but I am not yet an attorney ("one who is legally appointed to transact business on another's behalf") because no state has yet given me permission to handle other people's legal rights. *2 Phrased differently, I have more legal knowledge but no more legal power than my mom. *3 This is why not everyone with a J.D. actually takes the bar exam; there are an awful lot of jobs out there for which a bar certification is just superfluous.

To become an attorney, I have to pass some state's bar exam, which is typically two eight hour days in length. To pass the bar, I'll have to study everything I learned the last few years and even learn some new material I didn't have time to cover. Because this is America, there are half a dozen companies willing to sell you this kind of boiled-down legal education. I'll be getting very familiar with Barbri over the next few months.

When I pass the bar (fingers crossed), the state will certify me to represent the legal rights of my clients. As my Legal Profession professor likes to say, attorneys are "super-fiduciaries" because we are ethically disallowed from representing anybody adverse to our client. We're exclusively indentured servants in a world of conflicting legal interests. People go about this in ways ranging from verbal attack dog to gentle wordsmith, but the tie that binds is faithfulness to one person or group against all comers. I did not have any real understanding of this concept when I came to law school, and I'm sure I will spend the next several decades wrapping my head around it, but I have to admit to feeling both excited and terrified to look out for people in this way.

When?

In the US, a law degree is a three-year post-undergraduate doctoral-level overly-hyphenated program. It is sometimes combined with other degrees, like an M.B.A., M.P.H., M.D., Ph.D., or even an M.Div. A conventional three-year program typically ends in May, and most states offer a bar exam in August and in February. Those months are ostensibly to give people time to do all the bar prep coursework I mentioned in the last section.

Where?

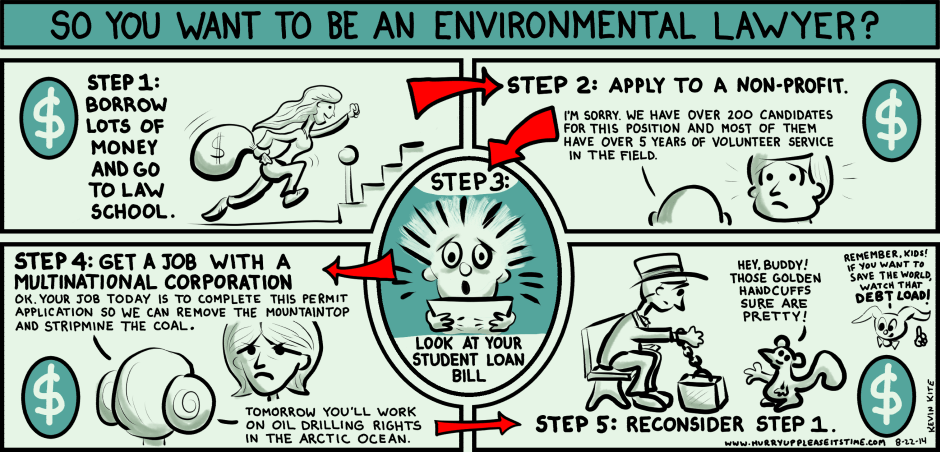

Ok, I'll brag a little here. I attended the University of Nebraska College of Law, which is ranked #56 overall and #2 in value in the United States. The core of that value comes from Nebraska's combination of insanely talented and well-accomplished faculty and extremely reasonable tuition and fees - I would bet that my average classmate spent less than half as much on law school as they did on their undergraduate degree. That's a really big deal, as the law school machine is notorious for trapping people in a cycle of debt, crazy jobs, and burnout. Attending a school you can actually afford isn't just a sound financial decision: it's a good idea for personal and professional reasons, too. I received a rigorous, well-rounded, and challenging education in my hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska, and had a lot of fun in the process. Lincoln is blowing up right now, and while I'll be sad to leave it behind I'm excited about my next opportunity (stay tuned).

Who?

I was definitely surprised by the academic diversity of my law school class, but I probably shouldn't have been. Of course, you run into plenty of political science, history, or English majors, but you'll also find an awful lot of people who studied anthropology, biology, chemistry, divinity, engineering, finance, German, humanities, international affairs, journalism, kinesiology (ok...I'm stretching), linguistics, music, nursing - you get the idea. The unifying factor is that everybody at this level did something well at an undergraduate institution and/or a career: how you did means much more to law school admissions folks than what you did.

This is "how, not what" mentality is reflected in the LSAT, the standardized test the schools use to rank their applicants. There is not one iota of substantive knowledge you need to bring into that test, unless you count the English language: unlike other exams, it is purpose-built to test your aptitude to apply the information they give you accurately and efficiently. This means that anyone with the desire and ability to learn quickly can theoretically be a great lawyer.

I was also surprised by the character, humor, and camaraderie I found among my classmates. I was proud to stand beside them as I received my diploma, and I look forward to watching them become leaders in the legal profession and society in general. If lawyers turn out to be rotten people, they certainly do not start that way.

|

| Love you guys. Also, I was serious - undergrad majors from left to right: biology, finance, political science, nursing, music. |

How?

There are basically three camps of "lawyers:" non-attorneys, transactional attorneys, and litigation attorneys. These people use their degrees in very different ways.

What I'm calling non-attorney lawyers are those who use their J.D. but lack or don't use their bar certification. These folks might be in anything from management to ministry, jobs that are sometimes called "J.D. Advantage" (rather than J.D. Required). These folks do not technically practice law, but they find ways to apply the skills and knowledge they pick up in law school.

Transactional attorneys are those who use both a J.D. and a bar certification but do not handle civil or criminal lawsuits. They draft contracts, keep folks updated on changing law, handle regulatory compliance, and perform other non-adversarial functions. Actually, you could call them anti-adversarial functions: a good transactional attorney adds value by saving her clients future legal fees by avoiding litigation. The stereotypical transactional attorney spends most of his time writing, but verbal communication within or between organizations can also be crucial skills.

Litigation attorneys are what most people probably think of as the prototypical lawyer: the folks who defend or prosecute their clients' interests in civil or criminal lawsuits. I can't find any good figures at the moment, but my understanding is that these folks are actually well in the minority compared to non-attorneys and transactional attorneys. This is the anywhere, anytime job in the legal profession: hours are long and variable in courtrooms, law offices, police stations, prisons, and just about anywhere in between. Litigators use their degree to draft motions and correspondence, conduct discovery, and speak in court.

Importantly, these are not mutually exclusive categories: some (if not most) attorneys cross between them on a daily basis. The employers are also widely varied - companies, law firms, individual clients (for the solo practitioner), governmental entities, agencies, private institutions, non-profits, and the list goes on.

Why?

We have a problem in this society. Believe it or not, lawyers are the solution.

On the one hand, everybody is bound by the law. The only way to keep the rules relevant is to enforce them. Everybody therefore theoretically needs to know the law so they can know how to avoid breaking it, or how to seek justice when somebody else breaks it. We also have rules about how we enforce the rules (things like civil or criminal procedure and evidence), and everybody needs to know those rules in order to ensure they get a fair shot in court.

On the other hand, we don't have time for everybody to go to law school. Trust me. As a society, we need the vast majority of people to do something else - grow food, fly airplanes, perform surgery, teach children, etc. Unfortunately, all those people are still governed by the rules because they have the capacity to put other people at risk every time they fertilize, pilot, suture, or even speak. Some people choose to take their legal rights in their own hands (called "pro se" representation), but this is generally a bad idea even for lawyers because the emotion and passion that comes in trying to vindicate oneself can be blinding even if you have the knowledge. As one potent potable puts it, "a pro se litigator has a fool for a client."

This is where attorneys come in: we're on-call advisers who dispassionately distill the law down into what a client needs to know, when they need to know it. My favorite explanation is simple: look the client in the eye and explain why "if you knew what the law says you're supposed to know, you'd do X." For some clients, that advice is all they seek. If they want to give us the discretion to act accordingly on their behalf, they can, but that is their choice because it is their life, freedom, or stuff on the line. In that way, it's not terribly different from medicine: you're perfectly within your rights to remove your own appendix, but it's generally advisable to get some help.

That's it.

I'll still be busy this summer, but I'll be firing up your regularly scheduled programming next week. Watch for weekly-ish articles, and keep up with me on Twitter or Facebook. 'Til then!

--

*1: A History of the University in Europe: Volume 1, Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2. Wikipedia.

*2: Webster.

*3: Happy Mother's day!